|

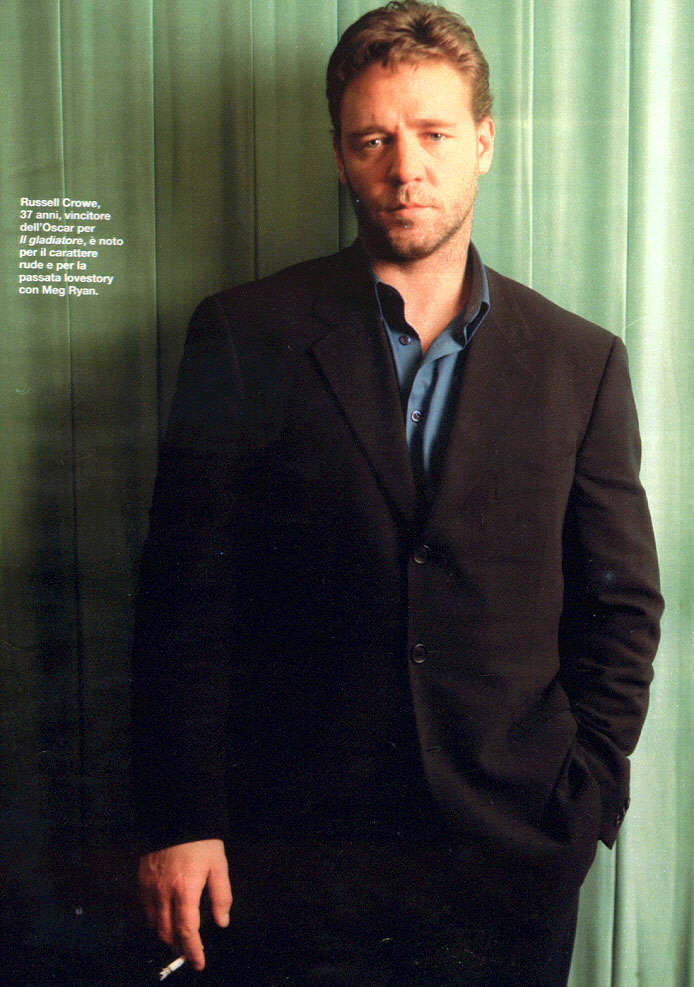

Russell Crowe

From gladiator to math genius. The latest metamorphosis

by the Australian actor, in the film A Beautiful Mind, is already stirring

Oscar buzz. And it also reveals about the man something which is even more

aphrodisiac than his rugged appearance: an extraordinary IQ.

by Anna Quadri, from the italian magazine "Io

Donna", 2002/01/12 - translation by luis

There’s no way of getting him to hide his biceps. A

heavy flannel working shirt (lumberjack style), sleeves rolled above his

elbows, and tight and threadbare jeans suit Russell Crowe at least as much

as bananas skirts suited Josephine Baker. He is the kind of man you would

turn to to have your car carburettor repaired. A rustic neighbour you would

call for help in hanging shelves on your living-room wall. For sure - on a

first glance at least - he doesn’t look like the sophisticated performer

often compared to extraordinary tough guys of the past, from Robert Mitchum

to Clint Eastwood, from James Cagney to Robert De Niro. You look at him - a

two-day’s beard, in a sort of Indiana Jones’s style, and sharp cowboy’s

manners - and you just can’t believe he is the subtle inquirer of human

psychologies able to deliver a performance which made America cry out in

wonder (Variety for one: “Crowe turns a strange and complicated guy

into a sympathetic and compelling character. We are witnessing an amazing

actor”). And there is not a single bookmaker who doesn’t regard his

nomination to this year’s Oscars as locked.

And yet.

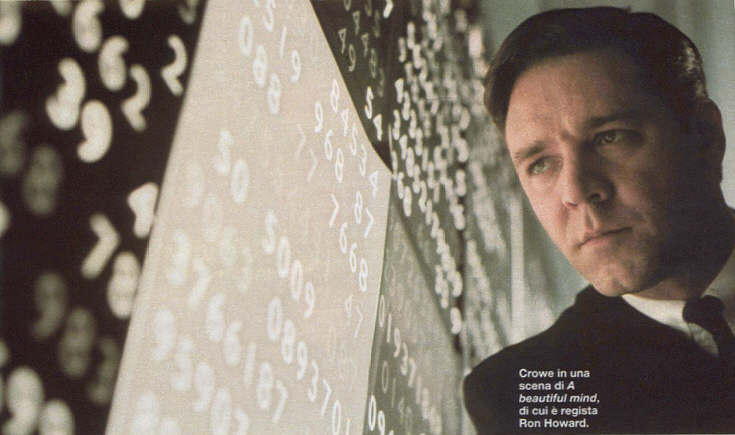

The film, A Beautiful Mind, directed by Ron Howard,

with an excellent cast from Jennifer Connelly to Ed Harris, to Christopher

Plummer, is based on the novel with the same title written by Sylvia Nasar,

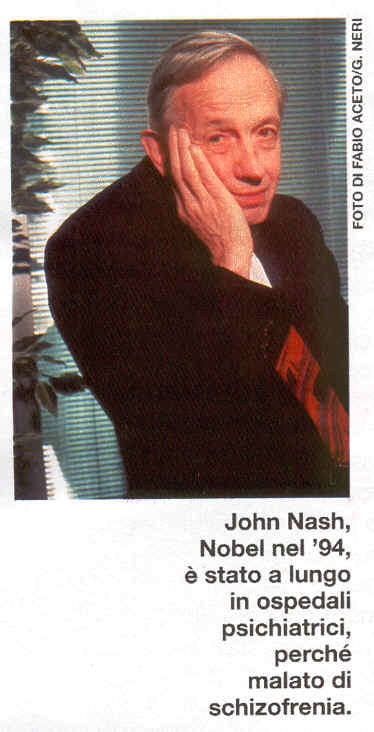

an accurate biography of the math genius John Forbes Nash Jr.

In the Fifties, Nash was the author of a revolutionary

theory which turned the ideas of Adam Smith and of other fathers of modern

Economics upside down. While he was at the very beginning of a brilliant

academic career, Nash fell into the abyss of schizophrenia; for almost forty

years he faced stints in psychiatric hospitals, the loss of his job, social

ostracism and - a perfect redemption for a Hollywood movie - he was

belatedly awarded the Nobel Prize in 1994. The gladiator flies over the

cuckoo’s nest. An experience which has made the only actor in Hollywood

who can claim Maori ancestry as sweet as a sugar candy and willing to

finally disclose an IQ which, in the business, is highly above the average.

As revealed in this interview Russell Crowe did for Io donna.

RC: Do you mind if I lie down? You may regard me as a

psychotic, after all this is what we are going to discuss.

He lies back on the cushions of an elegant antique sofa,

in one of the suites of the Dorchester Hotel in London.

ID: Go ahead. It’s still early for a diagnosis. And

then it is not the first interview I have done with people lying in a

Paolina Bonaparte pose.

RC: For example?

ID: Jennifer Lopez.

RC: Never tried a more uncomfortable sofa.

He sits in an armchair, as properly as an English Lord,

and laughs.

ID: Talent and genius: these are notions the film A

Beautiful Mind makes you think through. But it also makes you consider

the inevitable risks such conditions imply.

RC: If you possess a mind as Nash’s, you are at

risk. It is inevitable: your contemporaries cannot understand you, nor see

reality the way you do. And that gives you many problems both socially and

emotionally. But Nash fought the trend, he wanted to reach something

outstanding, for sure he was never a student who would stick to good marks.

ID: Is the close link, between genius and madness,

decreed by the silver screen - Shine, Rain Man, An Angel at

My Table, to name just some - a reality or it is just a commodity to

screenwriters?

RC: I think it was Edgar Allan Poe who said: “We

still don’t know whether madness is the higher form of intelligence”.

The fact is, though, that there are a lot of mad people around who are not

geniuses and most of the geniuses are not mad. The causes of schizophrenia

are not clear yet. In my opinion, mental illness is simply a part of

yourself, of your destiny. I see it that way, romantically.

ID: Acting requires talent, in rare cases we can even

say genius. You look very self-assured. Have you always been like that or

realizing that you were talented has also meant being overwhelmed by the

responsibility of goals to reach, of expectations to meet?

RC: The short answer is no.

ID: And the long answer?

RC: In the film Nash talks about the difference

between being a genius and being more than a genius. These are distinctions

you make when you talk about revolutionary theories, new scientific models

which allow new interpretations of the world, of events and of their

relations. Of an actor the most you can say is that he is good or very good.

Let’s say I am good: it is a result I have achieved slogging my guts out,

learning tricks, trying ways, training to be confident in revealing myself.

It is my job, being able to inquire into human nature and to express

emotions and weaknesses in a credible, moving way, trying to make the human

being an interesting subject. If I delivered, we can even say that I am very

good. But please, don’t go further.

ID: Then you think it’s all about practice. Don’t

you think you have been given a gift by nature or, if you are religious, by

God?

RC: I don’t know a single person who could

seriously talk about what God had given him without uttering bullshit.

ID: Here’s where the sourly fame and the media

curse comes from

RC: Have I been sour? I am just trying different

perspectives (giggles)

ID: Ron Howard compared your performance to the best

ones by Robert De Niro, underlining though that, unlike De Niro, you are

alien to the Actor’s Studio method and, another difference, you are very

friendly and collaborative on the set. Can you see yourself in that picture?

RC: Not exactly. I think that when Robert De Niro

began, someone must have asked him that same question, comparing him to

Marlon Brando. I don’t follow the Method as he does, I don’t make people

on the set call me with my character’s name and I don’t cloister myself.

Probably Brando was even stricter in his performances. But if you watch such

films as On the Waterfront or Raging Bull, you realize that,

no matter what kind of weirdness they did or what mood they inflicted on the

crew, if that was necessary to achieve that result, than certainly that was

the way it had to be done.

ID: You didn’t want to meet Nash before filming, is

this part of your more relaxed attitude compared with those of your famous

forerunners?

RC: De Niro would have grilled him for days. But that

wouldn’t have been of any use to me: Nash battled his disease, I don’t

know if we can say he has recovered from it, but after 35 years of

electroshocks and medications he cannot give many clues to an actor who is

going to play a schizophrenic ageing from 20 to 65. Material on Nash is

really not much, since he has never had a social life and since he spent a

large part of his life in hospitals, but there’s plenty of documents on

the disease. I watched dozens of documentaries on it, I have become familiar

with its external manifestations, I have tried to understand the way a

schizophrenic sees reality, a path the audience gets to walk along in the

course the film, getting inside Nash’s mind.

ID: Yet the film has a very optimistic approach to

the disease, making us believe you can recover from it.

RC: That is not true. It deals with the way a

brilliant man was able to rationally control his nightmares, his obsessions,

through his brain. He has probably learnt to live with them somehow, which

has made him socially acceptable. And worthy of the Nobel Prize.

ID: For an actor mental illness is a fatal attraction

and a sure Oscar bait. Is this the reason why, after working with brilliant

and unpredictable directors such as Michael Mann and Ridley Scott, you

decided to work in a blockbuster movie with a conciliatory director as Ron

Howard?

RC: Ron Howard might be conciliatory in Splash,

but I think no one can imagine what he is able to do when working on a story

about schizophrenia. He is a great director, who is in command of the

medium, but willing to collaborate with the people he is working with; he is

brilliant and complex, but he is able to simplify things when needed. He

could be resting on his laurels, instead he searched for a difficult project.

You will change your mind about him. And as far as the Oscar is concerned,

didn’t you notice I got it last year?

ID: And this year many Australians will be among the

nominees, Nicole Kidman for one. The number of your fellow-citizens working

in America is increasing. Ridley Scott said that for Gladiator he

needed an intense actor, but also someone full of dignity. And added that no

American possessed such qualities. What is it that’s so irresistible about

you Australians?

RC: I’ve never examined the issue closely, but I

have the feeling that we are regarded as British actors with an exotic touch.

Australia doesn’t offer much to an actor, the market is small, the

facilities are old, so almost everyone works and learns on the theatre

stage. Thus, as the British, we are disciplined, professional and focused.

Even a second-rate actor in Australia has read the Brönte, Molière and

Shakespeare. I have even read Little Women.

ID: A rarity.

RC: When I say so, the Americans start to laugh. We

antipodeans have all the advantages of being Down Under and being able to

look at what happens in the heart of the empire from a privileged

perspective, deciding if and when we want to take part in it. For this

reason I believe that flying to and fro between my farm and the studios is

the ideal solution. And then, if you become the king of the frequent flyers

supertop, the better.

|